003 Investment Companies & managers

Chapter 3 of 'There are no grown ups'

The ‘Trader’s option’: bet the ranch, if you lose, you get fired, if you win, you get a vast bonus, promotion, etc. Losses are paid for by your employer / clients, but you get to keep a slice of the gains. Heads they lose, tails you win. Welcome to the world of ‘money management’. The 2008-9 crash saw this approach scaled up from the individual money manager to the whole sector: winning bets were cashed in, loosing ones were bailed out by the taxpayer, after conveniently allowing the bankruptcy of Lehman brothers, which had been competing quite successfully with the better-connected Goldman Sachs, informally known as ‘government sachs’.

Investment banks & hedge funds are well aware of the divergence between their interests and the interests of individual staff. They put a lot of effort into managing the risks this creates, in particular not allowing a ‘bet the ranch’ type trade. George Soros was able to put on his winning big bet against the Bank of England because he was the boss. He was right on that one, and on his subsequent bet on French interest rates: he had publicly said he would not be betting against the French Franc, but he did not need to; currencies & interest rates are so closely linked that a position in one is usually a very close proxy for the other. If you think that Manchester United are going to miss qualifying for the champions league next year, but are not allowed to bet against the team (eg because you are one of their players), an alternative might be to bet on a decline in super-prime property in Alderley Edge, a village favoured by northern footballers: if you were the pessimistic player cited, maybe you would sell your mansion, (using the smokescreen of an alleged relationship breaking up, as cover for your your decision to sell).

Investment management, running money for other people, is a very odd business. Public disclosure requirements force most investment managers to publish details of their main ‘positions’ ie, the stocks / bonds in which they have invested most heavily. It is possible that a publicly disclosed holding is hedged (the risk is offset to some extent) by other, undisclosed (because they are small enough not to be reportable), positions. For example a money manager that thinks oil is set for a terrible time, but that Exxon is the best placed major to ride out the storm, might buy Exxon while selling BP, Shell, Total, etc. , with the large ‘long’ Exxon position being published & the several linked ‘short’ positions on other oil companies being below the radar. So beware! That said, if you are looking at a conventional long-only manager (ie one that just buys and sells stocks/bonds and does not use derivatives or ‘sell short’ things that they don’t actually own) these risks can be minimised.

If your research makes you have confidence in 3 or 4 managers, you could monitor their main holdings, and just make your own fee-free investments in those stocks. Such a strategy is likely to outperform giving 1/3rd or 1/4 of your money to each of them: they will execute better, but, almost certainly not by enough to offset the 1.5%-3+% annual management fees you are saving. If you hold a stock for 5-10 years, relative to paying a money manager to buy and hold it for you, the compound cost of management is probably 1.0155 = 1.0773 (ie 7.7%) to 1.0310 = 1.344 (ie 34.4%). You can do a lot of mis-timing of your buying & selling, and still have cash left over relative to paying 34% in fees!

Despite the possibility of using publicly available information to get a ‘free ride’, this is unlikely to be the best strategy for someone who does not want to make their own trading/investment decisions. It could work as a filter, or otherwise as part of the selection making / evaluation process of an active investor who is running their own money, but, for most of us who see any value in the choices made by professionals, such piggybacking, while fine in theory, does not work particularly well, as it requires a relatively hands-on approach. So we are back to choosing an investment manager.

Most of the investment management sector involves client money being run by people & businesses that don’t have maximising client returns as their focus. Tim Price in ‘Investment through the looking glass’ characterises the high-profile fund management giants as ‘asset gatherers’ rather than ‘asset managers’.

Lest you think that I am too cynical, I mention meeting a very bright and engaging chap who, having taken the well-worn path via Goldman Sachs to setting up a hedge fund, noticed that he had lots of friends in similar positions. They had all bet on their funds succeeding, but knew success was not assured - it was all a bit of a gamble and, if they were unlucky, any of their funds might ‘blow up’ (which would make their clients unluckier still ..) . So, his idea was to create a partnership of 10 hedge fund proprietors, with each putting 10% of their business into the partnership, so that the proprietors whose funds ‘lost’ would have a safety net funded by those that ‘won’. All very rational risk management for the proprietors, but no comfort at all for their investors. Such a partnership would have the effect of insulating, the proprietors of funds from bad choices that wiped out their clients’ money.

As fasr as I can see, the ideal investment manager

- Has a single fund / single strategy

- Has a large chunk of their own / their family’s wealth in that fund

- Is not known to be dishonest and, ideally, is known to be honest

- Appears to by psychologically stable and able to master their emotions

- Has an investment philosophy that seems reasonable

- Has a reasonable fee structure

- Has run a business (other than an investment management business)

Single fund / single strategy

Having a ‘Single fund’ may be overstating things, the concern is that there should be a single strategy. It may be that, for regulatory reasons, different entities are needed for investors from different regulatory areas (typically USA, rest of the world), or to cater for the fact that some investors may want dividends automatically reinvested, while others want an income stream. But it seems right to find a management company that says ‘We believe that these are the right investments to deliver good returns without undue risk’. Karl Sternberg, who founded Oxford Investment Partners, managing money for several Oxford colleges, used to say “We tell clients, you are not special, you want what everybody wants. You might say you have a high-ish appetite for risk one day, but if I ask you the same question just after you have had a 10% loss, you will give me a different answer’. That makes sense. But the bigger point is that, when an investment company offers a range of funds, with different strategies / geographies, they tend to do so for marketing purposes, and, as discussed in Chapter 1, the labels that they attach, ‘high risk’ Vs ‘low risk’ etc are usually a long way from my understanding of common sense.

If I am going to say ‘you guys are the professionals, make the best investment choices with my money’, why would I want to say ‘make the best choice in the area of Italian corporate bonds?’. If I want to buy an Italian corporate bond, I can do my own research and buy the bond(s) I like. If I am paying someone else to make the choices, why tie their hands?.

But the main reason for favouring single strategy / single fund managers, is that the company running the fund has all its eggs in the one basket that is their fund. If their fund prospers they will win plaudits and grow, if it fails, they will be out of business. They have nailed their colours to the mast, which is the opposite of the big name retail fund managers who offer scores of funds, and regularly launch new ones. They do this for two key reasons. Firstly dishonest marketing: if you launch one fund betting that Manchester United will win the premiership, another that Chelsea will win, and another that Arsenal will win, etc, then at the end of the year you are pretty much guaranteed that you will have a successful fund whose impressive performance can be featured in advertising to attract customers next year. Secondly, it offers customers a choice that largely pushes on to them the responsibility for choosing a particular strategy. If the institutional view of the management company is that Arsenal don’t have much chance of winning, then it is hardly ethical to hire some poor deluded Arsenal enthusiast to run an ‘arsenal fund’ and to encourage foolish retail Arsenal fans to invest in the fund (this does not mean that backing outsider-Arsenal can never make sense, but someone can just pop down to Ladbrokes or betfair, and back Arsenal directly. If they already know they are backing Arsenal they don’t need to pay someone else to place the bet).

Personally invested

If a manager has most of their own wealth tied up in the fund, then their interests are aligned with those of their clients. They will not be cavalier about losses. The problem of the ‘Trader’s option’ is avoided. And, of course, the fact that they have significant investable funds of their own suggests that they are likely to have been successful in their prior endeavours (unless it is all inherited).

The Rothchild family’s multi-decade commitment to, and 20% holding (value c£600m) in, the RIT Capital Partners investment trust is a great positive indicator. A smaller & newer example of the same alignment of interests is seen in The Metropolis Value Fund which grew from the in-house management of surplus cash generated by the proprietors’ businesses.

Manager honesty

This is pretty self explanatory. Ask around and see if those who know the people running the show think they are honest in small things. The regulators will probably refuse approval to those that have been demonstrably dishonest on a large scale, so you are looking for the small things.

When I was at university I went to an event that promised food & wine, but on arrival, I discovered that they had run out of food, so I left and got supper elsewhere. The organiser tried to say that as I had entered the event I was obliged to pay (the cost went on the college bill). He later went in to the fund management industry, and a friend of mine running institutional money found themselves at a meeting where it was suggested his company should invest in the event-organiser’s fund. He did not need to say anything about the chap’s behaviour, instead he recused himself from the discussion explaining that he knew the manager personally and did not like him. Do you think they invested?

Appears to by psychologically stable and able to master their emotions

‘If you can meet with triumph and disaster, and treat those two impostors just the same’: Kipling’s prescription is echoed by many books on investment, so I was surprised when I read Victor Niderhoffer's book ‘The Education of a Speculator’ in which he described standing on a table and punching the air after a successful trade. But less surprised when, a few years later, I read that he blew up his fund in 1997.

Has an investment philosophy that seems reasonable

There are thousands of different funds out there. More than enough that chance alone will produce several with decade, or longer, runs of good performance. So, whatever their record, it is a good idea to understand a manager’s philosophy and have confidence in it, rather than simply trusting them to have an alchemical formula that somehow produces great returns.

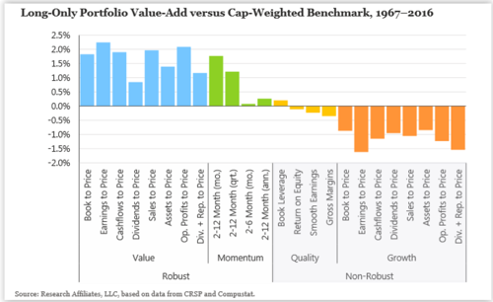

As to which philosophies seem reasonable, the table below shows cumulative returns of various strategies:

The table is a great starting point, as it can act as a cure for ones prejudices. While I trust fundamental analysis (looking at the attributes of the underlying security) more than technical analysis (looking only at price patterns), the data suggests that using technical analysis for a momentum strategy (systemic trend following) can work.

Has a reasonable fee structure

If you read the marketing materials, you could be forgiven for thinking that the key differentiator between investment funds/vehicles is their investment strategy. But, if you were to set out to buy an asset management firm, aside from looking at assets under management (ie how much cash it controlled), your focus would be on the charging structure / pricing. If there are two asset management firms, each with £1bn under management, other things being equal, if one of them achieves annual management fees of 3%, but the other only receives 1.5%, the first one will not be worth double the second, it will probably worth four times as much, or more. If both have costs of c1%, the first makes a pre-tax profit of 2%, while the second only has 0.5% falling to the bottom line.

The absolute level of fees is not the only issue. The structure of the investment fund can be very significant. Some structures are designed as products to be marketed to you: the people doing the marketing / selling to you are likely to be more interested in maximising their own commission/fees, than in how well your investments perform: and you end up paying for that marketing & (mis?) selling.

Hedge funds were initially funds that ‘hedged’ i.e. offset risk so allowing a more focussed strategic view. If a fund thinks that Tesco is particularly well managed and likely to increase its market share, it can simply buy Tesco shares. But, if the UK grocery market declines (due to recession, or disaster), they might still lose money even if Tesco is the best managed grocer and does grow its market share. The risk of losing money, despite being right about a company’s strength, can be reduced if the fund sells short (bets against) the shares of Tesco’s main rivals (Sainsburys, Morrisons, etc). That way, if the whole sector declines, the bets against Sainsburys & Morrisons will pay out. If the whole sector grows, the fund will loose money on the bets against Sainsburys & Morrisons, but, if Tesco does indeed have superior management that increases the Tesco market share, then the profits on the Tesco shares will more than offset the losses on the bets against Sainsburys & Morrisons. This sort of hedged view, which is arguably more conservative (if not better) than just buying individual shares, is not typical of the way hedge funds invest in practice. Hedge funds follow a wide variety of investment styles, some do hedge in the classic sense, but at least as many use derivatives, short selling, and leverage, to amplify risk exposure. The term ‘hedge fund’ tells you nothing about how the fund will invest, the only thing it really tells you is that it is has 2+20 (or similar) charging structure, hence the unkind, but accurate, description ‘A Hedge Fund is a charging structure with an investment strategy attached’.

When you buy a car, you probably know that, if buying new, the car will loose c10% of its value the moment it is driven out of the dealer’s showroom. ‘Front loading’ of marketing costs mean that many funds offer investors a similar ‘instant loss of value’ the moment they buy a fund. But not all funds are like that: investment trusts avoid the problem, unit trusts do not. Yet Unit Trusts are far more numerous. The reason that Unit Trusts (open ended investment companies) are far more prevalent than Investment Trusts (closed ended investment companies), has nothing to do with Unit Trusts being superior vehicles for the investor, and everything to do with what makes money for investment managers & advisors. Unit Trusts traditionally have a ‘front loaded’ fee: when you put cash into the fund c5% may be skimmed off the top, this fee is used for marketing & to pay ‘advisors’ who steer clients (you) into the fund. An Investment trust has no such marketing / sales budget.

Before the days of slick marketing of funds, and before the UK’s 1987 ‘Big Bang’ city deregulation that brought down dealing fees, Old fashioned retail stockbrokers were sometimes given what amounted to power of attorney to make buying and selling decisions with a client’s investments. This way, you, as the client, kept full and direct (or via ‘client account’) ownership of your money/investments. You were not buying an investment product at all, instead you were buying a service [Unfortunately, as brokers typically made (and make) their money from transaction fees / spreads when stocks are bought/sold, hyperactive over-trading was common. So much so, that it had its own name: ‘Churning’]. These days, most retail brokers, whether high street or online, would want to put you into funds rather than single stocks, so the approach is likely to add an extra layer of fees on top of the fund manager’s.

Has run a business (ideally other than an investment management business)

When travelling, being a bicyclist makes me a better car driver, and, being a car driver makes me a better bicyclist. Experiencing road use ‘from the other perspective’ is much more effective than just trying to follow the advice to ‘look out for cyclists’ or ‘beware that a car driver might not have seen you’. Similarly, being an investor makes someone a better manager, and being a manager is likeley to make someone a better investor.

It is difficult to run a business for any time, without gaining some understanding of what makes a business successful/unsuccessful. Even running an unsuccessful business can give someone amazing knowledge. Investment businesses are unlike most other businesses and so, understanding/running such a firm may not be quite as good a training.

Warren Buffett goes a step further, “I really think, if you want to be a good evaluator of businesses — an investor — you really ought to figure out a way, without too much personal damage, to run a lousy business for a while. I think you’d learn a whole lot more about business by actually struggling with a terrible business for a couple of years than you learn by getting into a very good one where the business itself is so good that you can’t mess it up.”

Unfortunately, if you add ‘must have run a lousy business’ to your other six criteria, you may find your choice of managers too limited. If they have run, or, better, started a business outside the field of money management, great. If the business they ran was a lousy one, count that as a bonus.

Experience of starting/running a money management businesses is better than never having run a business at all, but money management is a world unto itself, dissimilar to other professional services businesses, and having very little in common with manufacturing, the international trade in physical goods, or innovation in engineering/technology.

The tables following outline the logistics of various investment vehicles, and the incentives of the people you may encounter on the way

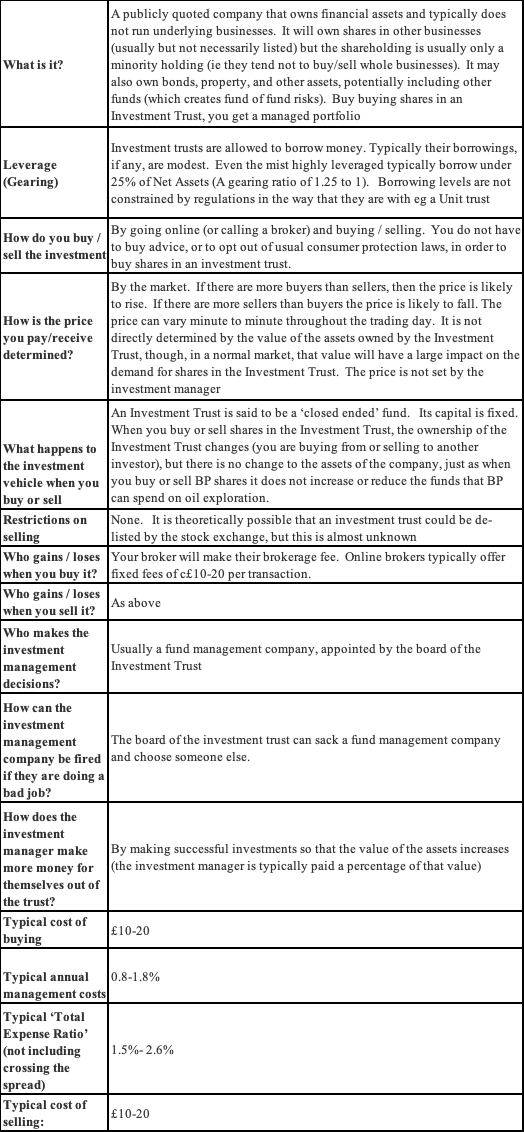

Investment Trust

[In the UK a REIT is a Real Estate Investment Trust. As the name suggests, it invests in property, typically owning property directly, rather than buying shares in other businesses. REITs are exempt from corporation tax but required to pay out 90% of profits annually]

Investment Trusts do not trade at exactly their book value (the value of all the shares they hold), while some trade at a slight premium, most Investment Trusts have traded at a discount to net asset values most of the time. That discount (premium) varies over time, discounts of c20% have often been seen, but should the discount get much larger than that, the trust may be subject to a takeover bid: If there is a trust with £300m of assets, with a market capitalisation of £210m (ie a 30% discount), then someone can make money by buying the whole thing and liquidating its holdings. Such a buyer will be able to acquire an initial stake at the deeply discounted market price, but, will then have to launch a formal takeover bid, and will typically have to offer closer to the underlying value for the rest of the company.

Buying an investment trust at a discount can be seen as a way of offsetting some of the cost of the manager’s fees. If management costs are 1.5%, and you expect a nominal return of 8%, if you can buy the Investment trust at a discount of at least 18.75%, then the management costs can be funded by the return on the ‘free’ shares (ie those you receive beyond the purchase price you have paid). Unfortunately, this ‘free ride’ becomes more difficult when expected returns are lower.

[The ‘breakeven’ calculation is: Management Costs / Expected Return = Discount that offsets management costs. So

2% management costs / 9% expected return = 22% Discount needed to offset management costs]

The interesting RIT Capital Partners Investment Trust unfortunately has, in recent years, traded at a premium (typically in the 5-10% range) to its book (or ‘Net Asset’) value.

Unit Trust / Mutual Fund / Open Ended Investment Company

What is it? | A vehicle, run & marketed by a fund management company, that receives investors cash, and then invests it. |

Leverage (Gearing) | Traditionally unit trusts were not allowed to borrow money. Now some are able to borrow up to 33%. This is a limit imposed by regulators so, if a unit trust was close to the leverage limit, and investments declined, the fund would be forced to sell assets to bring borrowing below the 33% limit. |

How do you buy / sell the investment | Either: By dealing with a Financial Advisor Or: Using an online ‘funds supermarket’ style platform. |

How is the price you pay/receive determined? | By the investment manager. Each trading day the manager (management company) assesses the value of the portfolio & comes to a view on the value represented by each unit in the fund. Some managers quote a single price, at which people can sell, or buy. Others have two prices: one at which they will buy units in from you, and anther (higher) price at which they will sell to you (where this occurs, the spread may include the c5% ‘front load fee’, or may be purely about the bid-offer spreads of underlying not-that-liquid investments). Setting a fair price requires two things for each underlying investment a) A reasonable basis for valuing it b) The ability of the fund to receive the estimated value should the investment (or part of it) need to be sold. c) If a share, or a bond, is publicly listed, (a) is easy (the market price may be an under or an ove valuation, but it is an objective fact that can be used), (b) is also easy, for the shares of large companies, for government bonds, and other securities that are highly liquid. Small companies, such as those listed on AIM, may be rather less liquid: The spread between the market bid and offer may be 5%, or more. And, if you want to buy or sell more shares than are traded on a typical day, you face the prospect of ‘the market running away from you’. If a fund invests in unquoted companies, or property, valuation is difficult, and should it be necessary to sell (or buy more) of the investment, there are likely to be high dealing costs, a need to ‘cross the spread’, and, very likely, delays (possibly significant), in the transaction if the manager wants to avoid selling at ‘fire sale’ prices, or paying a huge premium. Most of the time, most managers do not find it difficult to quote a daily price. Unfortunately, the times when they do find it difficult, may coincide with when you want to sell. See the ‘restrictions on selling’ section for more details |

What happens to the investment vehicle when you buy or sell | When you buy, the investment vehicle receives cash, and the manager deploys that cash When you sell, the investment vehicle must pay cash out to you. If they don't have enough cash pay you, the manager must sell investments to realise cash. If the fund is leveraged, it may have to sell more than £1 of investments for every £1 you redeem. Much of the time, the cash needed to pay those selling units in the fund, can be found from new investors. If one Wednesday new investors want to put £500,000 into the fund, and existing investors want to withdraw £500,000, then the manager does not need to buy or sell any underlying securities. The new money from new investors, is simply paid to the existing investors, and the fund has to do nothing other than to register that £500,000 worth of the fund has different owners. When there are more people buying units than selling them, the fund manager gets new cash to invest. Where investments are in minority stakes in large quoted companies, the manager can easily scale up each holding pro rata (ie if new money makes a fund 5% larger than it was last week, the fund manager can just by 5% more BP shares, 5% more Berkshire Hathaway B shares, 5% more Amazon shares, etc). If the investments are in unquoted companies, such scaling up is likely to be difficult at best (and, potentially, involve transaction fees that, in fairness, should not be funded by long term investors in the fund who have already paid the transaction costs when the fund bought its initial holding in the unquoted company), and potentially impossible to execute at a reasonable price. And, if the fund owns property directly, it cant increase its holdings of the property already owned (eg if there is only one building at 100 Park Avenue, and the fund owns it, then there is no more property at 100 Park Avenue to buy), and so will, at best, buy similar property. For all but the largest funds, property, which may be a very good long term investment, comes with the complication that it comes in much larger ‘chunks’ than shares. Even if 101 Park Avenue is available to buy, the purchase might fundamentally re-balance the portfolio. Lets say that we have a £200m fund, with 15% (ie £30m) invested in office property in the form of 2 office blocks, each worth £15m. This fund is successful, and new investors mean that the managers have a further £20m to invest. To keep the existing allocation ratios of the (successful so far) portfolio, would suggest 15% of £20m ie £3m going into new property. But, without c£15m, the fund can’t buy another office block similar to the existing ones that have proved to be successful investments. For a fund manager, having to deploy new capital is ‘a good problem to have’, even if it comes with a few complications. Less good is what happens when there are more people selling units than buying them. When this happens, the fund manager needs to sell assets to raise cash to return to investors leaving the fund. If they have to sell some blue chip shares, that's easy, as such shares have 3 great virtues - They can be turned into cash very quickly - The fund’s act of selling is unlikely to cause the price to deteriorate (If cUSD 3+ Billion worth of Apple shares are traded each day, then even a USD 100 million disposal would hardly be noticed) - The cost of disposal (dealing cost / crossing the spread) is unlikely to be large If they have to sell shares in a smaller company, then, at best, they will be likely to have to cross the spread. The well regarded micro cap Smart (J) & Co Contractors, symbol SMJ, has a bid at 110 and an offer at 120, a spread of more than 8%): a month can go by with less than GBP100k of shares traded, so getting out of a large position quickly would necessitate a price cut. When one gets to unlisted assets, whether property, or shares in private companies: selling at anything like the usual willing buyer-willing seller price takes time, and costs money. If you had to sell your house, you would pay fees to an estate agent, and would also expect to give them weeks if not months to find a buyer willing to pay what you think the house is worth. Even if your next door neighbor with an identical house had just sold at £500,000, if you called an estate agent on Wednesday, asking them to sell your house by Friday, you would probably be lucky to get £375,000: few people looking to live in the house would be able to act that quickly, so the only buyers would be vultures planning to flip the house. It would be the same for a £10m or £100m office block. Privately held companies are no more liquid: it takes time for any fresh investor to do due diligence, and time/brokerage fees to find that investor. For funds that are not mostly invested in large-cap equities (or highly liquid government securities such as Gilts, US Treasuries, JGBs etc), the moment the fund has to start making large disposals of illiquid assets, the wheels are likely to come off, and the regulatory requirement that the fund manager posts a daily price at which they are prepared to buy/sell becomes a vast burden beset with conflicts of interest. Consider a USD250m fund that lists a fair price based on underlying Net Asset Value, and then is hit by a USD 50m redemption. To fund that USD50m, it may have to sell assets that it has valued at USD75m. So the remaining investors, who yesterday owned USD200m of the funds assets, now own USD175m. And, if the fund has just disposed of is more liquid holdings, the remaining USD175m of assets might require fire-sale pricing to liquidate quickly. Lets say that the fund manager really believes in the underlying investments, and that USD175m is a conservative (pessimistic) valuation in normal times, but that, in a fire-sale, they would raise only USD125m. If the manager quotes a price based on the USD125m, then investors who 36 hours earlier owned USD200m, are now looking at a 37.5% loss if they need to get out and, even if they don't want to get out, they face the possibility of dilution by new investors coming in and, in effect, getting the fire sale prices by buying the fund at a discount. If the manager tries to avoid this, and quotes a price based on the underlying USD175m ‘fair value’, switched on investors who have just seen what has happened with the USD50m redemption, will have a big incentive to get out fast, just as, if you fear a run on your bank, you need to get your money out first. Your incentive is threefold - The USD175m price is based on ‘fair value’, while if you wait, and there is a rush of withdrawals, you will end up getting the fire-sale value - If the fund’s initial investment choices were well chosen and resulted in a balanced, diversified, set of holdings, the rush to fund the USD50m redemption, would not have resulted in an across-the-board sale of 1/5th of the holdings. The least liquid would have been kept, and the most liquid sold. The remaining holdings would have an illiquidity bias - Fund managers, who are paid a fee based on the notional value of assets under management, would be facing a big fee cut. If the fund is part of a big organization, ‘star traders’ would be likely to be focused elsewhere. The fund may even be merged with another fund. If you initially invested because you believed in the strategy and the manager Being an Open Ended investment vehicle is a structure that only works well when the fund is growing, or going sideways. |

Restrictions on selling | Because the open ended structure works badly during times of heavy selling, the normal rules are often suspended if investors start wanting to withdraw lots of money. If you really want to sell, at a time when lots of other people also want to sell, you may be faced with a ‘redemption gate’: literally the gate is closed to withdrawals to prevent a run on a fund and/or to allow the fund time to dispose of assets in an orderly way (giving the estate agent a month or two to sell that house at a fair price, rather than having to accept a fire-sale price from a vulture), or a ‘liquidity fee’: if not banned from selling entirely, the fund manager may say ‘if you sell, we will have to offer a 20% fire sale discount to liquidate quickly, so we are passing that 20% on to you as a fee’. |

Who gains / looses when you buy it? | If you are paying an entry fee (typically up to 5%, and sometimes incorporated into a bid-offer spread), then your advisor / broker / platform will benefit from this. The fund management company does not necessarily share in that fee although, funds that use a 3rd party (eg advisor-broker etc) sales channel may have agreed with the channel that they will not undercut the 3rd parties (so people don't get a recommendation from their advisor, and find that by going online and buying direct they save 5%: such a structure would not have advisors queuing up to recommend the fund to their clients). The ‘not undercutting the channel’ strategy means that, where you buy the fund online directly from the fund manager, the manager can pocket the 5% as extra profit. Because different advisors & platforms compete with each other, they may offer discounts / rebates on the c5% usual fee, in which case it can be cheaper to buy via the intermediary than to buy direct Once the purchase has been made, the fund management company will gain ongoing management fees for as long as you hold the fund. |

Who gains / looses when you sell it? | If you sell, the fund will have less capital under management, and so the fund manager will receive less in management fees going forward. Where a fund quotes a bid and an offer separately (rather than publishing a single daily dealing price), then to the extent that you have to cross this spread to sell your holding, the person/business on the other side (eg the fund management company or, possibly, the platform) will gain, especially of they benefit from a large trading volume and are offsetting your sell order against a buy order from another investor. If your decision to sell triggers, or helps to trigger, the sort of large scale liquidation & fire sale described in the ‘ What happens to the investment vehicle when you buy or sell’ section, then the fund manager may face a significant impairment to their business. Staff there may loose their jobs, almost certainly they will get smaller bonuses. And, if the liquidation involves fire-sale disposals, the vultures buying assets cheaply ae likely to gain (unless the market is about to head south and, what the vulture thought was a bargain, ends up being valueless. See the brilliant Film Margin Call with Jeremy Irons & Kevin Spacey) |

Who makes the investment management decisions? | The investment management company |

How can the investment management company be fired if they are doing a bad job? | Hmm. Usually, for all practical purposes, they can’t. |

How does the investment manager make more money for themselves out of the fund? | By making the fund bigger: they get paid a fee that is a percentage of the funds value each year. Some mutual funds may have a performance fee on top of the basic ‘assets under management’ fee, but, even where this is the case, most fund management companies would rather have twice the assets under management, rather than achieve twice the annual return for their investors. |

Typical cost of buying | Up to 5% |

Typical annual management costs | Management fees of: 0.75-1% in the UK (1.5% used to be typical, not least because perhaps 0.25% p was being given as a kickback ‘trail commission’ to the advisor who sold the fund) Plus trustee, auditor, etc fees running to another 0.1-0.2% Potentially plus performance fees of up to 20% of performance above inflation/the index |

Typical ‘Total Expense Ratio’ (not including crossing the spread) | 1.25%- 2.75%[5] |

Typical cost of selling: | With an online broker, the transaction costs may be minimal. The fund manager may impose an ‘exit fee’ (aka ‘repurchase charge’ or redemption charge). Before buying a fund, check to see if the manager imposes an exist fee, and be very careful to check the wording: promotional materials that say ‘We currently do not have an exit charge on any of our funds’ are no help if the small print gives the manager the power to impose such a fee later. |

Hedge Fund

What is it? | A hedge fund is an open ended investment vehicle, although, some hedge funds close their doors to new investors when they reach a certain size. If your strategy is to be nimble, move money quickly, and take advantage of price discrepancies between markets, it may work with USD 250m under management, but try to make that USD 2.5Bn, or USD 25Bn, and the strategy will not work if the markets are not ready to take bets that are 10x, or 100x, as large. Hedge funds dealing with major currencies, government bonds, interest rates, and futures/swaps/options based on them, face almost limitless liquidity, and so are may not be constrained by size in the way that a stock arbitrage fund might be. Hedge Funds are a subset of the Open Ended Investment fund market, in many ways structurally similar to Mutual Funds, but set apart by - Regulatory status, who can invest & minimum investment - Lock up periods - Liquidity restrictions (typically no daily dealing price) - Leverage / use of derivatives - Strategy: bets Vs investments, shorter holding period - Charging structure |

Leverage (gearing) | Most Hedge funds deploy leverage, sometimes vast amounts. Leverage of thousands of percent is not unusual. LTCM had 2,500% (A gearing ratio of 25 to 1) even if only comparing their $4.8bn equity capital with the $125+bn in assets. Those assets included derivative products involving an underlying notional $1.25 trillion ($1,250 billion). |

How do you buy / sell the investment | In the UK, USA, & most other jurisdictions, the first step before buying into a hedge fund is to certify, or prove, to the fund manager (or an introducing intermediary) that you meet ‘professional / accredited / sophisticated investor’ criteria based in your net worth / income / being (now or previously) a regulated investment professional. This status, as well as being a prerequisite for hedge fund investment, typically excludes you from the usual consumer protection regulations[6]. These are products for rich people / institutions that can afford to loose the whole of their investment. To some people, such warnings only serve to burnish the allure of Hedge Funds: the idea that being admitted to invest in a hedge fund is a badge of success, of admission to a high-rolling club, creates a non-financial incentive in terms of boosted ego. Those that sell hedge fund investments know this, and will use it to their advantage whenever they can. If you find yourself being flattered, remembering that they want your money and don't like or care about you as an individual, may help you resist. Making a large investment for non-financial reasons[7] is likely to be disastrous. Being accompanied by your spouse, especially if you have been married a long time, may serve as a brake on rash investments, but under no circumstances should you see an investment salesperson accompanied by someone you want to impress, such as a recently acquired girlfriend or boyfriend. Actually avoiding dealing with salespeople altogether is probably wise (as detailed elsewhere in this book). Most Hedge Funds have a minimum investment of US$100,000, or more (USD 1 million is not unusual). While an investment trust or unit trust may hold a balanced portfolio of stocks, allowing you to think of the investment as already diversified, this is not usually the case with a Hedge Fund. So, if you want the risk-reducing benefits of diversification, you might be looking at 5+ hedge funds. Even at $100,000 each that would be $500,000. |

What happens to the investment vehicle when you buy or sell | Although the sums may be typically larger, and the charging structure more lucrative for the investment manager, the mechanics of what happens to the money when you buy/sel are similar to those seen in humbler Open Ended Investment Companies (Unit Trust / Mutual Fund): |

Restrictions on selling | Lock in periods are common. While some hedge funds will be quite flexible for outgoing investors, others have only a single ‘redemption day’ each month, or even each quarter, on which investors can sell. If the fund includes illiquid assets that can’t be sold quickly, selling may be more a process than an event: You might get 90% of the proceeds quite quickly (within 30 days) but have to wait much longer (until after the annual audit, or until an asset can be sold) for the final 10% Funds holding illiquid assets may also impose a ‘gate’ that maximizes the amount that can be redeemed on any particular redemption day. Investors are usually treated on a first-come-first-served basis, so that if you ask to redeem but the gate threshold has already been met/exceeded, you will be told you cant sell on the redemption day. If you are lucky you will then be first in the queue for the next redemption day next month/quarter. |

Who gains / looses when you buy it? | The Fund manager gains by getting your money on which they expect to charge fees. If you are paying a 2% per year management fees, and hold he fund for 5 years, even if it makes no money, then the fund’s manager will have pocketed c10% of your initial investment |

Who gains / looses when you sell it? | As above, the fund manager sees a revenue stream leaving (they may make something from the exit fee, if there is one – see on) |

Who makes the investment management decisions? | The investment manager / management company |

How can the investment management company be fired if they are doing a bad job? | Generally they cant |

How does the investment manager make more money for themselves out of the fund? | The good way: They grow your investment, and so get to charge you 2% of a larger number in future years. On ‘success’: They get a ‘performance fee’ of 20% of the gains (or gains over a threshold, such as inflation, or central bank base rates, or the index). This is all very well when the success is down to great judgment, but what if all the fund has done is to borrow money and track the index with a 3 (or 5, or more) times leverage? In good years it will do 3 times as well as the index, in bad years, it will loose 3 times as much. |

Typical cost of buying | All being well, you have a good chance of avoiding ‘front load’ fees. After all, once you have invested, you will be paying royally for the privilege. If you are particularly unlucky you may pay to get in. |

Typical annual management costs | 2% of assets + 20% of profits Sometimes 1.5% of assets + 15% of profits |

Typical ‘Total Expense Ratio’ (not including crossing the spread) | There is a lot of truth in the saw that ‘A Hedge fund is a charging structure with an investment strategy attached’[8]. Talk of a ‘typical hedge fund’ is pretty meaningless. Other than the charging structure, two different funds may have almost nothing in common. A Long Only Equity fund may have more in common with a Unit Trust than a Global Macro fund, or an Arbitrage fund. The investment style will determine the level of investment turnover, with some hs hedge funds having very high rates of turnover, so the cost of dealing fees, etc can be much higher than in a typical mutual fund holding its average investment for 15 months. |

Typical cost of selling: | Most funds will impose, at the very least, a ‘soft lock up’ fee of 2-3% on investments redeemed within a year (this is better than the ‘Hard Lock up’ of a prohibition on selling within the first year) |

Venture Capital Trust

What is it? | A venture capital / private equity fund typically pools the cash of investors and uses it to invest in early stage companies. The fund structure can be a) Listed; in the UK this may be as a Venture Capital Trust (which has tax benefits) b) an unlisted private fund making investments that, in the UK, typically attract Enterprise Investment Scheme tax relief. c) An venture investment specialist putting investors into individual positions that are held directly by the investor, though with the investor typically represented by the venture capital specialists |

|

Leverage (gearing) | As these are usually deemed to be high risk investments against which banks will not lend, the fund/investments tend not to be leveraged, albeit that the companies getting venture capital equity may be taking in debt as well as equity, in which case there is de-facto gearing (though no more than when an un-leveraged unit trust buys shares in a company like CocaCola or BP, which issues corporate bonds as well as equity |

|

How do you buy / sell the investment | For a listed venture capital trust, you deal through the exchange (eg via online broker). For an unlisted pooled investment you either approach the fund directly (if HNWI / sophisticated investor) or you may be referred by an IFA (more usual for a ‘retail investor’). At least that is how you buy. Selling is not so easy. These investments are typically illiquid, with most investors making tax-favoured investments on which the tax relief would be lost in the event of early withdrawal, and for which there is hardly any market (those interested are keen to get then tax relief by investing directly rather than buying off the initial investor) | |

What happens to the investment vehicle when you buy or sell | The investment vehicle is typically open ended. On buying, it gets cash, which it then uses to invest in newly issued shares. | |

Restrictions on selling | Being ‘locked in’ for 5+ (often 10-14) years is usual. It may be that you can only get out (other than at a fire sale price) when the underlying investor company is sold or listed. | |

Who gains / looses when you buy it? | If you were referred by a financial advisor, they will get a commission. The fund management company will extract a fee when the cash goes into its fund and/or when the fund uses the cash to buy shares in an investee company. The investee company probably also gains when your cash filters into its account and can be used as working capital to fund growth. Those people gaining employment in the investee company probably gain, as do those in the supply chain serving that company. If the investee company goes on to disrupt a costly market, the entrenched providers (and their staff / supply chains) may loose out. | |

Who gains / looses when you sell it? | If you need to sell ‘early’ or quickly, you are likely to loose, and any gain would go to a (probably vulture) buyer.!! | |

Who makes the investment management decisions? | The investment management company | |

How can the investment management company be fired if they are doing a bad job? | Typically they can not | |

How does the investment manager make more money for themselves out of the trust? | More size, longer holding, successful exit fees Also, after perhaps 3yrs of active investing, the investment manager can sit on their hands doing very little for 7-10 years, until exit. During this time they still collect the hefty 2%pa fees (plus charging investee companies for director services of their nominees) | |

Typical cost of buying | The cost is opaque as, as well as any entrance fees charged by the investment manager to the investor, the manager is probably charging a fundraising / marketing fee to the investee company. You may ask ‘if the investment manager is retained by the investee company & paid a fee to raise capital (at a price the company finds acceptable), and is also employed by the investor and paid a fee to deploy the capital into good companies at the best possible price for the investor, is there not a conflict of interest? Is the manager working for the company (which wants to give away as little equity as possible for the cash it needs) or for the investor (who wants to get as much equity as possible for their cash)? The answer is: neither. The investment manager is working for the investment manager. | |

Typical annual management costs | The investor will usually pay c2% of ‘assets under management’, as the assets are usually illiquid their value is difficult to determine: try to sell quickly and you will find that you get out rather less than you put in. As you may have guessed, the deemed value, on which the investment manager charges their fee, is often assessed ‘generously’: unless an investment is made into a company that actually goes bankrupt, expect the ‘value’ to be deemed to be at least the purchase price, unless and until something gives the investment manager an excuse to put a higher price into their model. If a company has raised £100m at £1 per share, the investment manager will be taking £2m pa (2% of £100m) in fees. If a year later the company raises another £5m at £2 per share, you can expect the original investors deemed ‘assets under management’ to have risen to £200m, so the annual management fee on that rises to £4m pa. Within 30 months, the £5m of new investment revived by the investee company will have been matched by an extra £5m of fees charged to investors by the investment manager. As well as charging fees to the investors, the investment manager is likely to be charging fees to the investee company for ‘directors services’ of one of their favoured people to sit on the investee company board and ‘represent the investors’ (ie represent the investment manager). | |

Typical ‘Total Expense Ratio’ (not including crossing the spread) | The total expenses tend to add up to an impressive amount of any investment, not least as ‘success fees’ may be charged on a deal by deal basis, so an investment manager that makes 5 loosing investments & has a big winner yielding a 500% return (ie, on balance only just achieves breakeven) can end up taking a big slice of the 500% as its ‘success fee’. As you might have guessed from the investment manager’s initial ‘riding both horses’ approach to fundraising, in which the manager can be paid by both the investor and the investee company, when there is a successful exit, the investment manager likes to get two bites of the cherry. The investor is expected to pay perhaps 20% of the profit (this is often called the manager’s ‘carried interest’), while the investee company, grateful for the fundraising, has given the investment manager warrants (call options) to buy stock at a big discount to the price expected for a successful exit. Lets look at a 10 year holding period ending with a successful exit (perhaps the fate of 1 in 6 or 1 in 7 investments) Fees on the way in 10% Annual fees 10 x 2% pa = 20% (possibly more if subsequent funding rounds validate a higher value on which to charge annual fees). Exit success fee (carried interest) 20% Exit warrants 10-20%. On this basis you may as well say to the investment manager ‘suggest an investee company to me, and I will buy two shares, one for me and one for you’. Don’t make the mistake of thinking that the investor does not pay for the warrants: if the investee company was not giving warrants to the investment manager, the company would have been prepared to give more equity to the investor for their money. I make 2 observations here A) Venture capital is often given tax advantages (in the UK, the Enterprise Investment Scheme, & Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme, deliver tax relief on the way in and exemption from capital gains tax on the way out), but almost the entire tax benefit, and possibly a bit more, is captured by the investment manager & the salesperson/advisor. (B) one reads about the success that US university endowments have had with VC and PE investments. These investments were not necessarily via funds or paying the same level of fees suffered by private investors. In at least some cases (and I don’t know the proportion) they are likely to have been given an opportunity to co-invest without paying fees eg if a Harvard man was making an investment (personally or on behalf of a fund they were managing) they may have called the investment committee at Harvard and offered them the chance to come along for the ride without paying fees | |

Typical cost of selling: | Within a fund, or for a privately held share that achieves an exit, there will be significant fees to lawyers, etc to effect the sale transaction. On sliver sling Is that formal dealing fees / exit charges are not usual. | |

Other | When dealing with venture capital or private equity businesses, manager alignment is particularly important. Be extra careful if there is a bank or conglomerate as a ‘parent company’ to the VC fund. From time to time the fund may back an amazing winner, one that can return not just 10 tines the investment, but 100 times. You can bet that, when that happens, if there is a big parent enterprise, and the fund is looking at the investment which has grown 10 times already and has the potential to grow much much more, there will be a vast temptation for the VC to push for the investee company to be acquired by the VCs parent. The investors are told ‘look at how well we have done for you, enjoy spending your profits’ while the parent company scoops the really big win. I have seen Asia Healthcare Trust (parent conglomerate: Dahbur ) try to pull this stunt with a very successful chain of opticians: imagine their disappointment when German Esslar also bid for the company The article https://techcrunch.com/2017/06/01/the-meeting-that-showed-me-the-truth-about-vcs/ is instructive, and highlights the fact that ‘Most funds, while only actively investing 3-5 years, are bound to 10 years. Many newer studies are showing that 12-14 year funds are more accurate for today’. So, having spent 3-5 years investing, the fund then waits c5-11 years to sell its holdings. During those 5-11 years, it does very little, other than collect a cumullative 10-22% of the funds’ value in annual management fees. | |

Fund of Funds

A ‘Fund Of Funds’ is typically an open ended investment vehicle (like a unit trust or mutual fund) that invests in other funds, rather than directly in shares, bonds, property, or other assets.

If you are the trustee of a charity, perhaps because you are part of your Parochial Church Council, you may have to make investment decisions. Even if you are tempted to run the money yourself, that is not going to happen. You will have fellow trustees, they may be very nice people, and may even be prepared to put in lots of time, but working as a committee with them, to make active management trading decisions?

Unless your charity has embraced passive (index) investment (which it probably should), there is a very persuasive sales line: ‘Just as picking a single stock requires analysis, skill, and judgement, so does picking a fund. And you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket. So get a professional manager to choose a selection of good funds for you’. This is persuasive because it is, broadly, right. But, getting that analysis/selection via a fund of funds unlikely to work well for you.

The fund of funds may have a ‘front load’ fee on entry (so you pay its front loaded fees, and then out of the money left they invest in funds that may have their own front loaded fees, leaving various managers ‘two bites of the cherry’ to the good, and you ‘two bites of the cherry’ down)

A fund of funds will always have an annual management fee. As will the funds in which it invests. Two layers of annual management fees, and possibly even success/’overperformance’ fees, is such a burden to carry, that it is almost impossible to overcome. I will do the maths in the ‘impact of fees’ section but, for the moment, keep hold of the idea that the fees you pay in a Fund of Funds have a good chance of exceeding the return you see.

If you want advice on choosing an actively managed fund, or a selection of such funds, then pay for the time of an analyst whose opinion you value. Expect to pay them handsomely, perhaps £500-£1,000 per hour. If such an up front overhead cost is prohibitive, which is likely if investing less than six figures, it may be a useful spur to reconsider the ‘boring’ option of index tracking.

Fund of fund of funds

Do the maths! (or wait till the next chapter when I will do them for you). With 3 layers of fees, what will be left for the poor old investor?

When is a Fund not a Fund?

When it comes to investing in publicly quoted stocks/bonds, paying someone else to make decisions hardly makes sense when those decisions are unlikely to yield better results (and may well yield worse) than what you, or the index, would achieve without their layer of costs. For unquoted investments, the position may be more complicated. In areas such as Private Equity, Venture Capital, specialist property development, etc, a fund management boutique may be doing much more than choosing where to invest money. They may be in effect running a banking or quasi banking business, and also getting involved in the management of the businesses in which they invest. Arguably, if dealing with such funds that are quasi banks, a ‘fund of funds’ could be analogous to a specialist banking fund. But, this is probably less a ‘justification’ for investing in such funds, than an illustration of the adage that a hedge fund is ‘A charging structure with an investment strategy attached’.

The strategy of maximum cynicism

One way to look at the structure and pricing of investment products is to begin by putting yourself in the shoes of the money manager, and then assume that the investor’s interests are likely to be the opposite of what makes life comfortable for the money manager. When writing this chapter, the temptation to rush out and set up a VC business was almost overwhelming. For the manager, the possibility of, de-facto, pocketing 50p of every pound that comes in for investment, is an attractive one. Especially when most, if not all, of that 50p is funded by tax breaks which distract the investor from how your game is played.